- Home

- Julie Schaper

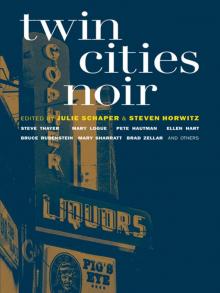

Twin Cities Noir

Twin Cities Noir Read online

ALSO IN THE AKASHIC NOIR SERIES:

Brooklyn Noir, edited by Tim McLoughlin

D.C. Noir, edited by George Pelecanos

Manhattan Noir, edited by Lawrence Block

Baltimore Noir, edited by Laura Lippman

Dublin Noir, edited by Ken Bruen

Chicago Noir, edited by Neal Pollack

San Francisco Noir, edited by Peter Maravelis

Brooklyn Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Tim McLoughlin

FORTHCOMING:

Los Angeles Noir, edited by Denise Hamilton

London Noir, edited by Cathi Unsworth

Wall Street Noir, edited by Peter Spiegelman

Miami Noir, edited by Les Standiford

Havana Noir, edited by Achy Obejas

Bronx Noir, edited by S.J. Rozan

New Orleans Noir, edited by Julie Smith

This collection is comprised of works of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors’ imaginations. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Series concept by Tim McLoughlin and Johnny Temple

Twin Cities map by Sohrab Habibion

Published by Akashic Books

© 2006 Akashic Books

ePUB ISBN-13: 978-1-936-07053-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-888451-97-9

ISBN-10: 1-888451-97-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2005934823

All rights reserved

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

[email protected]

www.akashicbooks.com

For Sylvia—olehasholiem

Acknowledgments

Thanks go out to all our bookselling friends, especially Pat Frovarp and Gary Shulze, Jeff Hatfield, Lyle Starkloff, Hans Weyandt, and Tom Bielenberg. Thanks also to Johnny Temple for giving us the opportunity, and to Johanna Ingalls for being Johanna Ingalls. And thanks to the Twin Cities writing community for their generosity and trust. If it weren’t for you, there would only be an introduction.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

DAVID HOUSEWRIGHT Frogtown

Mai-Nu’s Window (St. Paul)

BRUCE RUBENSTEIN North End

Smoke Got in My Eyes (St. Paul)

K.J. ERICKSON Near North

Noir Neige (Minneapolis)

WILLIAM KENT KRUEGER West Side

Bums (St. Paul)

ELLEN HART Uptown

Blind Sided (Minneapolis)

BRAD ZELLAR Columbia Heights

Better Luck Next Time (Minneapolis)

MARY SHARRATT Cedar-Riverside

Taking the Bullets Out (Minneapolis)

PETE HAUTMAN Linden Hills

The Guy (Minneapolis)

LARRY MILLETT West 7th-Fort Road

The Brewer’s Son (St. Paul)

QUINTON SKINNER Downtown

Loophole (Minneapolis)

STEVE THAYER Duluth

Hi, I’m God (Up North)

JUDITH GUEST Edina

Eminent Domain (Minneapolis)

MARY LOGUE Kenwood

Blasted (Minneapolis)

GARY BUSH Summit-University

If You Harm Us (St. Paul)

CHRIS EVERHEART Downtown

Chili Dog (St. Paul)

About the Contributors

INTRODUCTION

TALES OF TWO CITIES

Murder and mayhem are probably not the first things that come to mind when most people think of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul.

What comes to mind may be snow emergencies and sub-zero temperatures; Eugene McCarthy, Paul Wellstone, and Jesse “the body” Ventura; Dylan, Prince, and The Replacements; the Guthrie, Theatre de la June Lune, and Heart of the Beast; The Walker, St. Paul Cathedral, and The Mall of America; Mary Tyler Moore, Tiny Tim, and F. Scott Fitzgerald; Lake Harriet, Lake Como, maybe even Lake Wobegone, which, depending upon who you talk to, may or may not be real.

But not crime.

Everyone here has an opinion about what makes the cities different from each other and what ties them together. A type of social shorthand has developed over the years. Minneapolis is hip and St. Paul is working class. St. Paul is the political capital, Minneapolis is the cultural capital. St. Paul was built by timber money and Minneapolis from grain. There is some truth in these generalizations but the people who live here know it’s not as simple as that and it never has been.

You don’t have to look hard to find the darker underside.

St. Paul was originally called Pig’s Eye’s Landing and was named after Pig’s Eye Parrant—trapper, moonshiner, and proprietor of the most popular drinking establishment on the Mississippi. Traders, river rats, missionaries, soldiers, land speculators, fur trappers, and Indian agents congregated in his establishment and made their deals. When Minnesota became a territory in 1849, the town leaders, realizing that a place called Pig’s Eye might not inspire civic confidence, change the name to St. Paul, after the largest church in the city. The following verse appeared in the paper shortly after:

Pig’s Eye, converted thou shalt be like Saul.

Thy name henceforth shall be St. Paul.

St. Paul was a haven for cons on the lam in the 1920s and ’30s. Bad guys across the country knew about the O’Connor system. A criminal could come to St. Paul, check in with police chief John O’Connor, and walk the streets openly, as long as he or she promised to stay clean. Ma Barker, Creepy Alvin Karpis, Baby Face Nelson, and Machine Gun Kelley spent time in the cities. The system fell apart in the early ’30s, about the time that Dillinger shot his way out of his Summit Avenue apartment.

Across the river, Minneapolis has its own sordid story. By the turn of the twentieth century it was considered one of the most crooked cities in the nation. Mayor Albert Alonzo Ames, with the assistance of the chief of police, his brother Fred, ran a city so corrupt that according to Lincoln Steffans its “deliberateness, invention, and avarice has never been equaled.”

As recently as the mid-’90s, Minneapolis was called “Murderopolis” due to a rash of killings that occurred over a long hot summer.

Every city has its share of crime, but what makes the Twin Cities unique may be that we have more than our share of good writers to chronicle it. They are homegrown and they know the territory—how the cities look from the inside, out. Some have built reputations on crime fiction, others are playing with the genre for the first time, but all of them have a strong sense of this place and its people.

Bruce Rubenstein, Gary Bush, and Larry Millett illuminate the past—the Irish cops, politics, radicals, and mob guys.

David Housewright, K.J. Erickson, and Mary Sharratt observe cultures colliding and the combustion that friction can cause. Pete Hautman and Judith Guest show us how amusingly dangerous life in the cities can be. Quinton Skinner, William Kent Krueger, and Ellen Hart illustrate what we’re all capable of when lives are on the line.

In these fifteen original stories we see representations of the past, the present, and perhaps even a glimpse of the future. Maybe as importantly, we see who we are—Midwesterners, Minnesotans, and residents of the Twin Cities. We hope you enjoy reading these stories as much as we enjoyed putting this collection together.

Julie Schaper & Steve Horwitz

March 2006

St. Paul, Minnesota

MAI-NU’S WINDOW

BY DAVID HOUSEWRIGHT

Frogtown (St. Paul)

Benito Hernandez did not know when Mai-Nu began leaving her window shade up. Probably when the late August heat had first arrived—dog days in Minnesota. It was past 10:30 p.m. yet the tempe

rature was eighty-six degrees Fahrenheit in Benito’s bedroom and his windows, too, were wide open and his shades up. Just as they were in most of the houses in his neighborhood. That was one way to tell the rich from the poor in the Land of 10,000 Lakes. The ones who could afford central air, all their windows were closed.

The window faced Benito’s room. Through it he could see most of Mai-Nu’s living room as well as a sliver of her bedroom. Mai-Nu was in her living room now, sitting on a rust-colored sofa, her bare feet resting on an imitation wood coffee table. She was stripped down to a white, sleeveless scoop-neck T and panties. What little fresh air that seeped through the window screen was pushed around by an electric fan that swung slowly in a half circle and droned monotonously. It didn’t offer much relief. Benito could see strands of raven-black hair plastered to Mai-Nu’s forehead and a trickle of sweat running down between her breasts. Next to her on the sofa were a bowl of melting ice, a half-gallon carton of orange juice, and a liter of Phillips vodka. She was reading a book while she drank. Occasionally, she would mark passages in the book with a yellow highlighter.

Less than five yards separated their houses and sometimes Benito could hear Mai-Nu’s voice; could hear the music she played and the TV programs she watched. Sometimes he felt he could almost reach out and touch her. It was something he wanted very much to do. Touch her. But she was twenty-three, a student at William Mitchell Law School—it was a law book that she was reading. Benito was sixteen and about to begin his junior year in high school. She was Hmong. He was Puerto Rican.

Still, Benito was convinced Mai-Nu was the most beautiful woman he had ever known. A long feminine neck, softly molded moon face, alluring oval eyes, pale flesh that glistened with perspiration—she was forever wrestling with her long, thick hair and often she would tie it back in a ponytail as she had that night. Watching her made him feel tumescent, made his body tingle with sexual electricity, even though the few times he had actually seen her naked were so fleeting as to be more illusion than fact. Often he would imagine the two of them together. Just as often he would berate himself for this. It was wrong, it was stupid, it was asqueroso!Yet when night fell, he would hide himself in the corner of his bedroom and watch, the door locked, the lights off, telling his parents that he was doing homework or listening to music.

Mai-Nu mixed a drink, her second by Benito’s count, and padded in the direction of her tiny kitchen. She was out of sight for a few moments, causing Benito alarm, as it always did when she slipped from view. When Mai-Nu returned, she was carrying a plate of leftover pork stew with corn bread topping. The meal had been a gift from Juanita Hernandez. Benito’s mother was always doing that, making far too much food then parceling it out to her neighbors. She had brought over a platter of carne y pollowhen Mai-Nu first arrived as a house-warming gift. Benito had accompanied her and was soon put to work helping Mai-Nu move in.

It wasn’t much of a place, he had noted sadly. The living room was awash in forest-green except for a broad water stain on the wall behind the couch that was gray. Burnt-orange drapes framed the windows and the carpet was once blue but now resembled the water stain. The kitchen wasn’t much better. The walls were painted a sickly pink and the linoleum had the deep yellow hue of urine. Just off the living room was a tiny bathroom—sink, toilet, tub, no shower—and beyond that a tiny bedroom.

There was no yard. The front door opened onto three concrete steps that ended at the sidewalk. The boulevard between the sidewalk and curb was hard-packed dirt and exactly as wide as eight of Benito’s size ten-and-a-half sneakers. Mai-Nu had no garage either, only a strip of broken asphalt next to the house that was too small for her ancient Ford LTD.

“It is only temporary,” Mai-Nu had told Juanita. “My parents came from Laos. My father helped fight for the CIA during the war. They did well after they arrived in America—they owned two restaurants. But they believed in the traditions of their people, so when my parents were killed in a car accident, it was my father’s older brother who inherited their wealth. He was supposed to raise my brother and me. Now that we are both of age, the property should come to us.”

But six months had passed. The property had not come to them and Mai-Nu was still there.

Benito wondered about that while he watched her eat. Mai-Nu did not have a job as far as he knew, unless you would call attending law school a job. Possibly her uncle helped her pay the rent on her house. Or maybe it was her brother—Cheng Song was not much older than Benito, but he had quit school long ago and was now the titular head of the Hmongolian Boy’s Club, a street gang with a reputation for terror. They had met only once. Outside of Mai-Nu’s. She had been shouting at him, telling a smirking Cheng that he was wasting his life, when Benito had arrived home carrying his hockey equipment.

Benito was only a sophomore, yet his booming slapshot had already caught the notice of pro and college scouts alike. Several D-1 schools had indicated that they might offer him a scholarship if he improved his defense and kept his grades up, which Juanita vowed he would do—“¡Si no sacas buenasnotas te mataré!”Cheng hadn’t seemed impressed by the hockey player, but later he told Benito, “You watch out for my sister. Anything happen, you tell me.”

Mai-Nu took the remains of her dinner back to the kitchen. When she returned she mixed a third drink and retrieved her law book. She kept glancing at her watch as if she were expecting a visitor. The phone rang, startling both her and Benito. Mai-Nu went to answer it, slipping out of sight.

There was a mumbling of hellos and then something else. “Yes, Pa Chou,” Mai-Nu said, her voice rising in volume. And then, “No, Uncle.” She was shouting now. “I will not!”

Benito wished he could see her. He moved around his bedroom, hoping to get a better sight angle into Mai-Nu’s house, but failed.

“I know, I know…But I am not Hmong, Pa Chou. I am American…But I am, Uncle. I am an American woman…I will not do what you ask. I will not marry this man…In Laos you are clan leader. In America you are not.”

She slammed the receiver so hard against the cradle that Benito was sure she had destroyed her phone. A moment later Mai-Nu reappeared, her face flushed with anger. She guzzled her vodka and orange juice, made another drink, and guzzled that.

Benito wished she would not drink so much.

The next morning, Benito found Mai-Nu at the foot of her front steps, stretching her long legs. She was wearing blue jogging shorts and a tight white half-T that emphasized her chest—at least that is what he noticed first. He was startled when she spoke to him.

“Benito,” she said. “Nyob zoo sawv ntyov.”

“Huh?”

“It means ‘good morning.’”

“Oh. ¡Buenos días! ”

“I’m probably going to melt in this heat, but I really need to exercise.”

“It is hot.”

“Well, I will see you…”

“Mai-Nu?”

“Yes?”

Benito was curious about the phone call the evening before, but knew he couldn’t ask about it. Instead, he said, “Your name. What does it mean?”

“My name? It means ‘gentle sun.’”

“That’s beautiful.”

Mai-Nu smiled at the compliment. Suddenly, she seemed interested in him.

“And Cheng Song?” Benito asked.

“Cheng, his first name means ‘important’ and my brother certainly wishes he were. Song is our clan name. The Hmong did not have last names until the West insisted on it in the 1950s and many of us took our clan names. I am Mai-Nu Song.”

“What about Pa Chou?”

“Where did you hear my uncle’s name?”

Benito shrugged. “You must have told me.”

“Hmm,” Mai-Nu said. “Chou means ‘rice steamer.’”

“Oh yeah?”

She nodded. “‘Pa’ is a salutation of respect, like calling someone ‘mister’ or ‘sir.’”

“Why does he have a salutation of respect?”

“Pa

Chou is the leader of the Song clan in St. Paul. What that means—leaders are called upon to give advice and settle arguments within the clan.”

“Like a patrón. A godfather.”

“Yes. Also”—Mai-Nu’s eyes grew dark and her voice became still—“also they arrange marriages and decide how much a groom’s family must pay his bride’s family to have her. Usually it is between $6,000 and $10,000.”

“Arranged marriages? Do you still do that?”

“The older community, my parents’ generation, they really value the old Hmong culture. That is why they settled here in St. Paul. It has the largest urban Hmong population in the world. Close to 25,000 of us. They come because they can still be Hmong here. Do you understand?”

“I think so.”

Benito attended a high school where thirty percent of the student body was considered a minority—African-Americans, Native-Americans, Asians, Somali, Indians, Latinos—all of them striving to maintain their identity in a community that was dominated by the Northern Europeans that first settled here.

“It is changing,” said Mai-Nu. “The second generation, my generation, we are becoming American. But it is hard. Hard for the old ones to give up their traditions. Hard for the young ones, too, caught between cultures. My brother—he likes to have his freedom. I asked him, my uncle asked him, where do you go? What do you do? He says he is American so he can do whatever he likes. You cannot tell him anything. Now he is a gangster. He brings disgrace to the clan. Maybe if my parents were still alive…”

Twin Cities Noir

Twin Cities Noir